Stop trying to swing in jazz

What do we mean by the word swing in jazz?

Referring to swing in jazz Dave Brubeck tells the story that Miles Davis approached him at the end of a gig and murmured in his ear “You’re the only person in this group that swings.” Had Brubeck replied: “What, exactly, do you mean by swing?” I suspect he would have been given short shrift. But of course both musicians had an implicit understanding of the word without the need for analysis or elucidation.

But what does the word ‘swing’ mean in the context of jazz? And can it be taught?

Try googling ‘swing in jazz’ and you will encounter an array of words and phrases such as groove and feel, which are of little practical use to a learning musician. But can you actually learn such an elusive art? And if not, does that mean that I, as a jazz piano teacher, am unable to teach it?

I used the word ‘elusive’ but there is, in fact, a science to swing. The theory can be pinned down and explained, but whether or not the theory can be translated into practice is another matter.

For practical purposes swing is about the rhythmic placement of eighth notes (or quavers where I come from). We can then refer to the result as swung eights.

A good place to start is how not to swing in jazz.

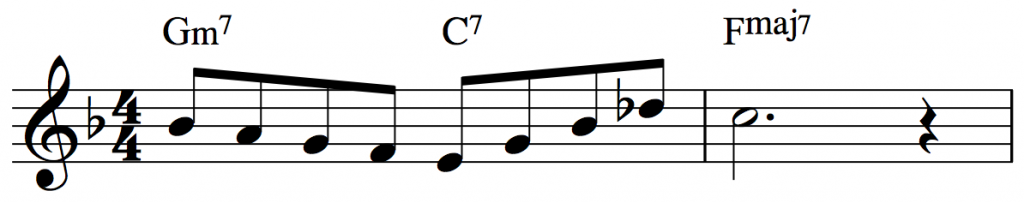

The following phrase mainly consists of 8 even eighth notes played over a II-V-I sequence in F major.

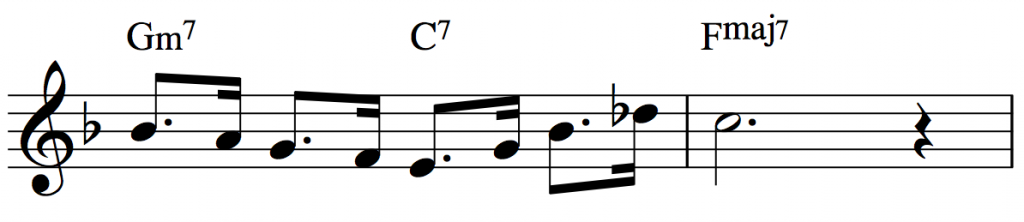

To convert this to a dotted rhythm is not the way forward as this leads to a stilted and artificial approximation of swing.

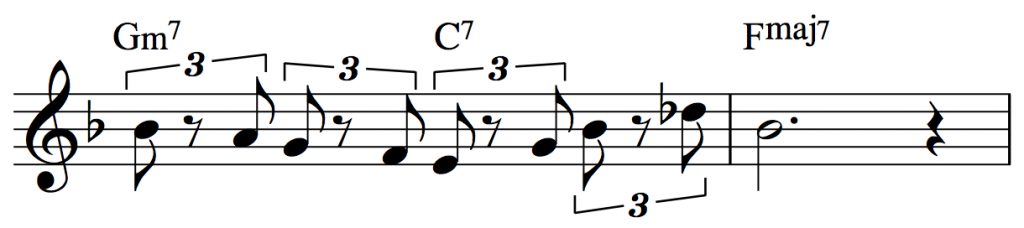

A more accurate representation is to introduce eighth note triplets that contain a rest midway.

This triplet feel could be shown as 12/8 as well as 4/4:

However, the convention is to show the notes as even eights (as shown in the first illustration) based on the assumption that the musician already knows that the piece has a swing feel.

Unfortunately, just to copy this rhythmic pattern will not result in a swing feel. The clue is in the word ‘feel.’ Bill Evans tends to play the eights smoothly; Hampton Hawes pushes them more. But both undoubtedly swing. Monk seems to swing even when he’s playing the melody of a standard. You can find an excellent example of Monk’s unique swing feel on YouTube in his live version of Don’t Blame Me (live in Denmark, 1966). His left hand is mostly playing a strict four to the bar stride, but pay close attention to his right hand phrasing. Although his eighth notes are anything but smooth, Monk never stops swinging.

Clearly, when we listen to the masters playing these so-called swung eights, the rhythmic placement seems to vary not just from player to player, but from bar to bar.

One could say that swing is a superimposition of two time signatures working in tandem: 4/4 and 12/8. And it’s the subtle shifts and use of dynamics that contribute to this swing feel. But we can’t escape the fact that the only real way forward is the combination of listening to the jazz masters and playing with other musicians.

Before I became involved in jazz I was playing rock music for many years. On occasion, when finding myself playing alongside classically trained musicians, I encountered another example of the difference in rhythmic feel: their idea of where the downbeat occurred differed from mine. I placed mine right on the beat whereas they seemed to place it slightly before. Neither is wrong. Nor does it imply that my downbeats coincide with the click of a metronome. Anyone with experience of programming music with the aid of a computer will know the dangers of quantizing: forcing beats into their precise slots dehumanises the music. In other words the human feel has been removed.

So how can swing be taught?

Firstly, we imbibe the swing feel by listening and playing with other musicians. Yes, I’ve said this before but I’ll keep repeating it.

Secondly it’s a question of rhythmic consistency. Some of the best sports men and women have been labelled as boring: Pete Sampras, Steve Davis, and, in the UK, even a football team: Chelsea. I would replace the word boring with consistent. And this consistency is achieved through moment-to-moment accuracy.

Over the years, my main self-criticism as a player has been my lack of consistency with regard to rhythmic accuracy. No amount of creativity will mask a lack of precision when placing notes. Until we are ‘locked in’ with the rhythm section, nothing will swing. And we can all instantly recognise whether or not a band is playing ‘in the pocket.’

A practical path to swing

I therefore encourage my students to sometimes think less about being creative and focus more on rhythmic accuracy. Here’s a good way to start:

- Play a constant stream of smooth eighth notes. At first it doesn’t matter which notes you play, as long as they are even. Don’t try to swing.

- Now leave some gaps between your phrases, but still hear and feel the 8s, even though you are not actually playing them. In other words this constant stream of 8s are always there ‘in the ether’ whether you’re actually playing them or not.

- Now try this with a simple II-V-I or turnaround sequence in different keys.

- Finally, try the above with a familiar jazz standard.

Learning to play a constant string of smooth and even eighth notes, over a bass line or ‘locked in’ rhythm section is the first step to achieving a swing feel.

From a teaching perspective, another essential part of the equation relates to levels of energy. Many of my students arrive for a lesson after a full-on day at work and are still buzzing with high energy. Some may also be stressed after driving through London traffic or as a result of being packed on to a rush hour tube train. While in this hyper or agitated state their playing is likely to be rushed and uneven and it can sometimes take 30 minutes before they settle down. I’m not suggesting that there is an optimum state that one should aim for in order to swing in jazz but, for me, I’m at my best when relaxed but alert. I can only describe this as a physically lower energy in the body.

Over my years as a student of jazz I have been given two pieces of advice that I always try to pass on. The first pearl of wisdom is the title of this piece: stop trying to swing in jazz. Put another way, if you make an active effort to swing the result will be stilted and artificial.

The second piece of advice was “stop trying to sound jazzy.” But that’s another article.

Here’s a link to my online video course.

And here’s a link to my Learn Jazz Piano eBooks.